They've already fought a battle that most if us will never endure, but for those who serve, the greatest fight of their life becomes when they get home.

Every 65 minutes, a veteran commits suicide after giving into the war within them — the daily internal battle of coping with PTSD.

The PTSD: National Center for PTSD reports: “Some studies that point to PTSD as a precipitating factor of suicide suggest that high levels of intrusive memories can predict the relative risk of suicide (9). Anger and impulsivity have also been shown to predict suicide risk in those with PTSD (15). Further, some cognitive styles of coping such as using suppression to deal with stress may be additionally predictive of suicide risk in individuals with PTSD.”

But it's not just older generations who are locked in a battle for their life, but younger generations, too.

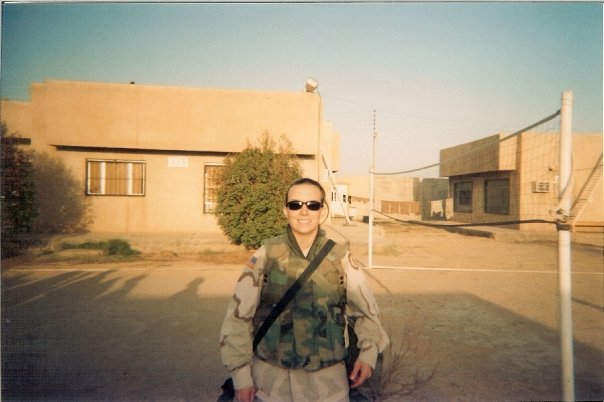

Derrick Burgan Jr. is just 31 but has been dealing with the aftermath of the horror of war since he was 22 when he was sent off to Iraq. By the time he was 25, he went to Afghanistan

Fighting in a war, he says, “was the last thing I wanted to do with my life.”

“My dad, two uncles, and my sister were all in the military so I wanted to do something different,” he says. “I went to college at Western Michigan and had a little too much fun. I wasn't going to school anymore and didn't have a job so I decided it was time to join the family business.”

Does he think he was mature enough to face the brutalities of war?

“No one is ever prepared or mature enough to see the fallout from war,” Derrick explains. “I was told by my family things I should expect which I guess helped a little. There is no way to accurately portray what really happens over there so there is no way to ever be ready for it.”

When Derrick came back to the U.S. in February of 2012, it was a shell shock to return to what is classified as “normal” life.

“In my opinion, normal doesn't exist anymore once you've been over there,” he says. “Civilian life is such a polar opposite of military life. Getting out and blending in is a scary and very difficult transition. I always felt like I was different and everyone could tell. I felt like no one would understand how I was feeling if I told them so I chose not to talk about it much. I also felt like a coward. All of my brothers and sisters that gave their lives for this country are the heroes. They gave it all and I ran after six years.”

He says that he had an overwhelming sense of isolation.

“It's a never ending cycle of survivors guilt, pride, and shame,” he explains. “The thoughts that go through your head make you feel insane and verbalizing those thoughts to people who have never been where you've been can make you sound insane to others. On top of that, I felt like showing that weakness would put a damper on the image the military built for me. Without my strength I felt like I was useless.”

And he tried to numb the pain.

“I started drinking alone really heavily,” he recalls. “Relationships didn't last long because I felt like I was alone in every relationship and felt like nobody understood me. I didn't want to change who I was. I didn't see a reason to. I felt like I had it all figured out but I didn't. I couldn't grasp the fact that I was no longer in uniform and that things weren't as simple as following orders and getting the job done.”

One of the largely ignored emotional aspects that emerges from anyone who has fought in war, is PTSD and this is something that Derrick has battled and battled with.

“I am 70% disabled through the VA for PTSD,” he says. “I deal with it on a daily basis. Depression sets in with a vengeance and can be extremely deadly. There are days where I would wake up with a pit in my stomach and a cloud over my head for no reason. I had the overwhelming feeling of failure even when things were going great. I never felt good enough. I also felt that I didn't deserve to say I have PTSD because there are people that have given far more for this country than I have and witnessed much worse. Its crippling at times.”

He continues: “For a while I was self destructive. I wouldn't allow myself to truly succeed. I didn't feel like undeserved to be happy. I found a way to screw up every great opportunity I had. I didn't do it on purpose but that's how it seemed.”

As an Audio Engineer and singer-songwriter, Derrick has found some solace in music.

“Music makes me feel like me,” he says. “I was lost for a long time and had no idea who I was or what I wanted. Music, even if just for a moment, made me real. It made my place on earth seem valuable. Knowing I can make music that may help someone not feel like I do makes it all worth it.”

That feeling of unworthiness seems to resonate with so many vets.

Michelle Slaughter, who served dual service from 1994 to 1998 and then 2000 to 2005, was rendered homeless for six months while she grappled with PTSD.

“The transition from military life to normal life is hard,” she says. “You don't feel like part of a team, you don't feel a sense of acceptance.”

It wasn't long before Michelle plunged to the depths of despair.

“Rock bottom for me was finding myself homeless bouncing from friend to friend and couch to couch. When not on a couch somewhere I was sleeping in my car. My PTSD symptoms and triggers affected my ability to work. I either didn't show up for my shifts or did not play well with others while at work. Transitioning into the civilian workplace is hard enough as it is then you add in emotional outbursts, hyper vigilance, nightmares, lack of sleep, and self medication to the mix and you have a recipe for disaster. I felt more shame, hopelessness, anger, and disappointment in myself than I did suicidal thoughts. I had them occasionally but never acted on them. ”

“PTSD has such negative connotations and with that, comes so many issues that we are dealing with. ”

Shame is a major issue that seems to stem from those who suffer from PTSD.

“I feel shame in that I have had issues with holding down jobs, failed relationships, or the many social anxieties and other issues that arise because of my PTSD.,” Michelle admits in all heartbreakingly brutal honesty. “The shame then leads to guilt because I can't hold down a job or that I have difficulty in large groups of people. It feels like a never ending circle at times.' WWP has been a huge factor in my life. Through their services I have connected with other Warriors that I can talk to, provided coping skills to help combat the shame or guilt, and helped with counseling services outside of the VA.

“People always come up to you and thank you for serving, but they don't know the price we have paid for serving our country.”

While music has provided Derrick with some comfort, Michelle has found the Wounded Warrior Project a haven, providing her with the coping mechanisms she needs.

She explains: “WWP has been a huge factor in my life. Through their services I have connected with other Warriors that I can talk to, provided coping skills to help combat the shame or guilt, and helped with counseling services outside of the VA. ”

Michelle and Derrick implore others suffering from PTSD to reach out and seek help.

“You're not alone, “Michelle explains. “Others out there are like you.”

Derrick concurs: “ASK FOR HELP! There is no shame in admitting you can't do it alone. Get help now. The longer you wait the deeper the rabbit hole goes.”

For Derrick, who recently welcomed his first child, Kindness & Hope are simple.

“Kindness is the only hope we have,” he says. “I pride myself on being kind to everyone I come in contact with. A strangers smile is therapeutic for me. Knowing that I may have been the one bright spot in someone's dark day gives me joy!”

To find out more about Wounded Warrior Project and to donate, click here

Annyira szeret, hogy fél attól, hogy emmiatt elveszít és azon gondolkodik, hogy elmegy orvoshoz. Nagy méretű, kényelmes bútor, melyet a modern formák kedvelőinek, nagy családoknak ajánlunk. A kamagra gold 1 milligramm készítmény nálunk amellett jóformán világszerte rendelvény nélkül megvásárolható. Saját érzékenységtől függ, ki hogy reagál az alkalmazására, ellenben normál esetben elmondható, hogy a mellékhatások sem idéznek előadja nehézséget. A magyarországi halálozások több mint a fele szív és érrendszeri betegségeknek tulajdonítható, ezek közül is a koszorúér betegség a legfőbb halálok.